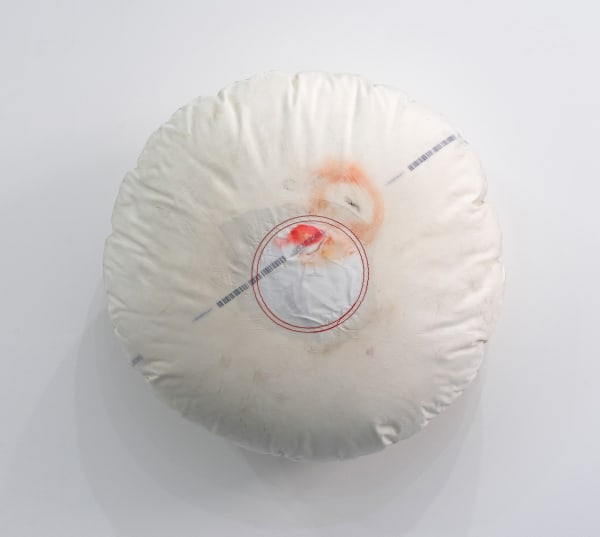

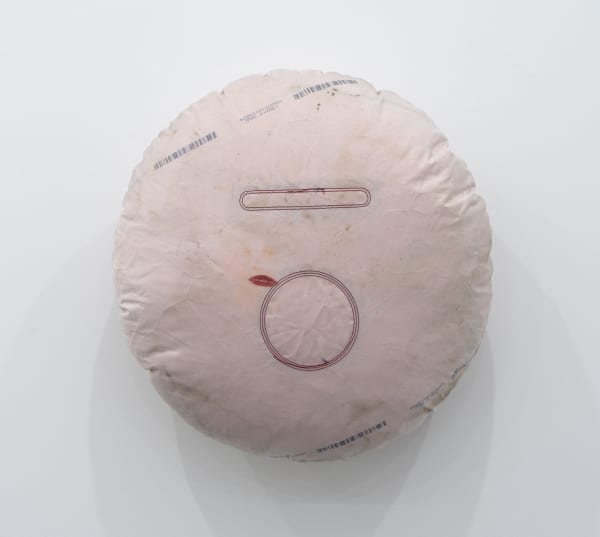

In Rubberneckers, Kevin Harman transforms salvaged airbags into unsettling portraits. Recovered from car wrecks, these objects carry accidental imprints of their drivers - traces of makeup, sweat, and hair pressed into fabric at the sudden moment of impact. Designed to protect life, they now record its fragility, collapsing protection and violence into a single surface. Once hidden within the mechanics of a car, the airbags now face outward in the gallery, resembling painted faces, ritual masks, or even taxidermy trophies. Their presence raises uneasy questions: are they artworks, relics, or residues of trauma? For Harman, collecting and reframing these objects carries the unsettling charge of a modern-day trophy hunter, turning safety devices into relics of catastrophe.

The works sit within a broader history of image-making. They echo the indexical trace of the Shroud of Turin and Yves Klein’s Anthropométries, where the body becomes both tool and subject. Yet unlike Klein’s choreographed performances, Harman’s portraits are produced involuntarily - in the unrepeatable violence of impact. This involuntary mark-making links the works to forensic photography, where the body inscribes itself without intention. Hovering between readymade, painting, and evidence, the airbags occupy a liminal space where materiality, accident, and representation converge.

At the same time, the works resonate with J.G. Ballard’s Crash, where technology and flesh collide to produce a new, troubling intimacy, and wounds take on sculptural qualities. Like Ballard’s protagonists, who discover a strange eroticism in vehicular violence, Harman identifies a perverse aesthetic in catastrophe: the crash site becomes a studio, the gallery a repository of its traces. Handling and presenting these objects situates Harman as both mediator and witness, compelling us to confront the uncomfortable reality of trauma made visible.

The exhibition’s title, Rubberneckers, underscores this tension. It refers to the compulsive act of slowing down to look at roadside accidents - a forbidden gaze that fascinates and repels. In the gallery, Harman re-stages this moment, positioning the viewer as both witness and voyeur, complicit in the same disaster tourism that clogs highways and feeds our appetite for spectacle. These are not idealised portraits but involuntary ones, marked by fragility, distraction, and risk. Each airbag contains residues of travel and collision, everyday journeys violently interrupted. By making them visible, Harman transforms private trauma into public display, raising questions central to Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others: What are the ethics of displaying trauma? Who has the right to look, and what responsibility comes with witnessing? The exhibition asks us to confront not only the aesthetics of catastrophe but also our own complicity as spectators.

The works sit within a broader history of image-making. They echo the indexical trace of the Shroud of Turin and Yves Klein’s Anthropométries, where the body becomes both tool and subject. Yet unlike Klein’s choreographed performances, Harman’s portraits are produced involuntarily - in the unrepeatable violence of impact. This involuntary mark-making links the works to forensic photography, where the body inscribes itself without intention. Hovering between readymade, painting, and evidence, the airbags occupy a liminal space where materiality, accident, and representation converge.

At the same time, the works resonate with J.G. Ballard’s Crash, where technology and flesh collide to produce a new, troubling intimacy, and wounds take on sculptural qualities. Like Ballard’s protagonists, who discover a strange eroticism in vehicular violence, Harman identifies a perverse aesthetic in catastrophe: the crash site becomes a studio, the gallery a repository of its traces. Handling and presenting these objects situates Harman as both mediator and witness, compelling us to confront the uncomfortable reality of trauma made visible.

The exhibition’s title, Rubberneckers, underscores this tension. It refers to the compulsive act of slowing down to look at roadside accidents - a forbidden gaze that fascinates and repels. In the gallery, Harman re-stages this moment, positioning the viewer as both witness and voyeur, complicit in the same disaster tourism that clogs highways and feeds our appetite for spectacle. These are not idealised portraits but involuntary ones, marked by fragility, distraction, and risk. Each airbag contains residues of travel and collision, everyday journeys violently interrupted. By making them visible, Harman transforms private trauma into public display, raising questions central to Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others: What are the ethics of displaying trauma? Who has the right to look, and what responsibility comes with witnessing? The exhibition asks us to confront not only the aesthetics of catastrophe but also our own complicity as spectators.